Ed Ruscha

View All WorkSince the early 1960s, he has focused on L.A.—its culture, architecture, and industry as the primary subject of his work. His iconic images of freeway gas stations, film studio logos, palm trees, swimming pools, and numerous other symbols of Southern California life both reflect and shape contemporary perceptions of Hollywood as well as the city that supports it. As a result, the artist has helped introduce a new, West Coast sensibility to the landscape of contemporary art, and helped establish a novel image of the artist as a Hollywood-style celebrity.

Characterized by low-key humor and drawing from “real world” source material, Ruscha is one of the original—one might say “founding”—Pop artists. Following his 2004 Whitney retrospectives, Roberta Smith, an art critic for the New York Times wrote, “these shows confirm Mr. Ruscha not only as a first-generation Pop artist, but also . . . a Post-pop innovator on a par with Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke,” while Peter Schjeldahl (another art critic) called him “one of the four most influential artists to have emerged in the nineteen-sixties, along with Andy Warhol, Donald Judd, and Bruce Nauman.”

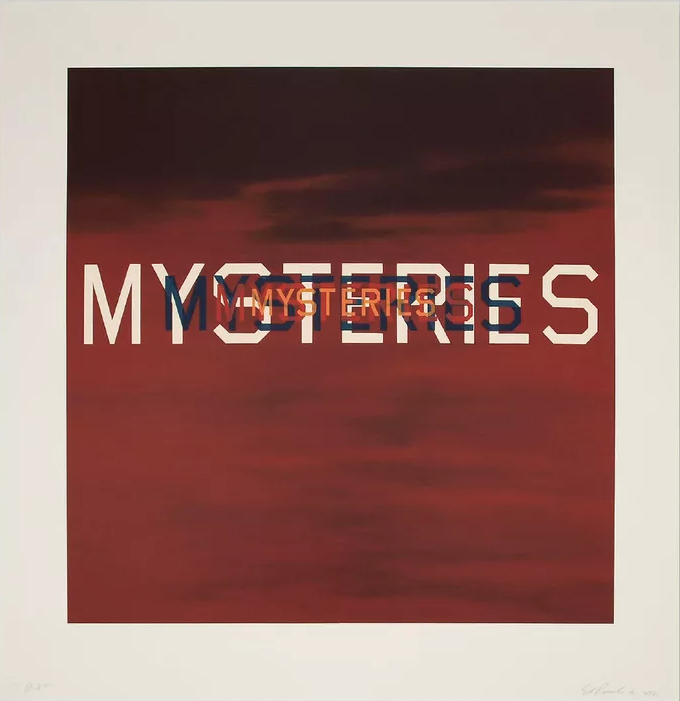

Ruscha’s work can’t be beat for poetic economy. When he draws a picture of the HOLLYWOOD sign in a smooth orange sunset, you get the feeling that he might have designed the original, or at least chosen the font. When in another drawing the sign reads HOLLOWEEN, you can tell that he is enjoying his cleverness to the point of bragging.

His self-confidence is undeniable and quite justified. The interest in Ruscha’s work is so passionate it could be considered a cult. Surpassing the established cult of linguistic irony firmly in place all over the art world, Ruscha’s best work is not just flat and removed—it’s confrontational and deep. His painting, emboldened with the phrase: “I don’t want no retrospective,” makes fun of the art world, but not before implicating Ruscha himself. We notice the colloquial double negative, but we also notice the Latin root (Ruscha’s hope for the future) and the hot pink it’s painted on. His rejection has perfect rhythm, and, for anyone who cares about which artist gets a retrospective, it’s also an indictment. In this work, as in all of Ruscha’s art, he is either a funny preacher or a serious comic, but either way, we get the joke.